Two Takes on the U.S. Midterm Elections

It looks like it will be a standard midterm outcome. It is not a standard moment in American politics.

This past week I was asked to give a couple of talks to non-American audiences about the state of American politics. I have delivered plenty of presentations like this over the past decade or so. Last week was weird, though. From an American politics perspective, it was a straightforward presentation. From an American political development perspective, what I said last week sounded pretty apocalyptic.

On the one hand, there is analyzing the midterms using the standard American politics toolkit: looking at economic fundamentals and presidential popularity. Those numbers look grim for Democrats. Inflation is higher than at any point in the last forty years. Real wages have declined over the past year. In response, the Fed has jacked up interest rates, making lots of folks nervous about a coming recession.

All of this is happening while Democrats control the House, Senate, and executie branch. Biden’s approval ratings are even with Trump and lower than Obama’s during the same point in their presidencies — and both of them suffered pretty serious losses in their midterms. As Charles Franklin and John Sides explained earlier this month, by the fundamentals the Democrats should lose close to 40 seats in the House and a cluster of Senate seats.

Elections are about more than fundamentals, of course. For a few months during the summer, Republicans seemed to be on their back foot following the Dobbs decision. GOP intra-party squabbling was high. And Biden got some bills passed. With the fall, however, it looks as though wayward GOP voters started flocking back to their party. Biden’s plan to run on his record did not seem to test well; with fresh news about a weak economy, voters want to know about future plans. Maybe polls are off, or maybe the ostensibly higher-quality polls showing better numbers for Democrats turn out to be more accurate. Still, the likeliest outcome at this moment in time is unified GOP control of Congress.

If this was ten years ago, or twenty, or further back than that, such a result would be unremarkable. It’s the standard rhythm of American politics; in the postwar era, the party out of power does well during the midterms. That has been particularly true during the post-Cold War era.

Even if the rhythm is standard, however, the moment is not. And that is the problem. The inconvenient fact of this election is that one party is running on a platform of flawed policies while the other seems to be running on a platform of fixing nonexistent flaws in institutions to cement their grip on power.

There is simply no getting around the fact that Donald Trump has successfully colonized the GOP over the past six years. With the partial exception of Mitch McConnell, no GOP member of Congress has opposed Trump and seen their political fortunes rise as a result. The transformation has been dramatic. And with Trump comes Trump’s ethos — refusing to acknowledge losses, delegitimizing unfavorable election outcomes, and threatening violence or chaos if there is a political reversal.

Given Trump’s track record, this is rather extraordinary. Ordinarily a president whose actions cost his party control of Congress and lost re-election would have been discarded as fast as you can say “George H.W. Bush.” That should hold with particular force if that leader refused to concede and fomented a violent assault on the Capitol building.

Instead, Republicans blinked in January 2021. Kevin McCarthy mended fences with Trump less than a month after January 6th. Mitch McConnell did not support impeaching Trump for his actions on that day. Trump’s role as kingmaker helped elevate either unqualified or unhinged candidates like Hershel Walker or Kari Lake to be nominated by the GOP. In some of these cases, Democrats (believing it was 2010 and not 2016) aided and abetted the crazy GOP candidate in the primary, on the logic that this would boost their chances in the general election.

If the Republicans do well in November, the takeaway for them will be that there is no longer any cost to behaving badly on the national stage. Bungle a pandemic and lie about the means to ameliorate it? Who cares. Nominate folks who ran on the faulty premise that Trump actually won 2020? No big deal. Support violence to compensate for losing at the polls? Big whoop.

It’s not that voters are blind to these issues — it’s that enough of them don’t care. As Blake Hounshell noted in the New York Times ten days ago following one of their big polls with Siena, “71 percent of voters agreed that democracy was at risk.” The problem comes with the rest of that sentence: “only 7 percent said that democracy’s fragile state was the most important problem facing the country.”

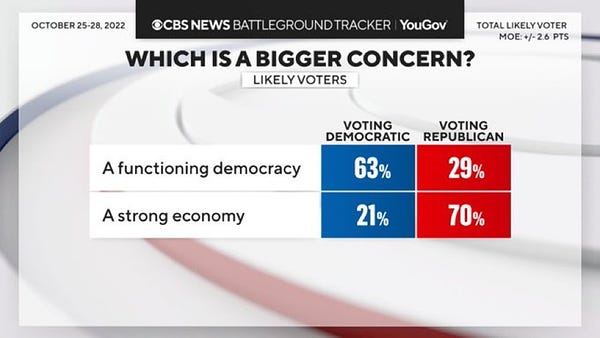

The New York Times poll is hardly the only outlet to report some variation of that result:

In other words, roughly half the country is implicitly okay with extralegal means of achieving political power. The rhetoric associated with that kind of belief leads to outcomes like the governor of Florida amplifying far right discourse about “the regime.” It softens the ground for the violent attack on Paul Pelosi last Friday. As the Washington Post reported:

For many Democrats, the attack on Nancy Pelosi’s husband represents the all-but-inevitable conclusion of Republicans’ increasingly violent and threatening rhetoric toward their political opponents — a phenomenon that escalated under former president Donald Trump, who prided himself on his inflammatory oratory and who was often reluctant to denounce white nationalists and others spewing hate speech….

For a wide swath of Republicans, Pelosi is Enemy No. 1 — a target of the collective rage, conspiratorial thinking and overt misogyny that have marked the party’s hard-right turn in recent years.

Among far-right extremist groups, the anti-Pelosi memes are often cruder and more violent, but the demonization of the Democratic House leader is no fringe phenomenon. Her face — sometimes adorned with devil’s horns or a swastika — was plastered on signs at all the national rallies that led up to the Jan. 6 storming of the Capitol. Pelosi is such a frequent target that it’s common for right-wing pundits and protesters to refer to her only by her first name, as Jan. 6 insurrectionists did when roaming the halls of the Capitol searching for her while yelling: “Where are you, Nancy?”

Call me crazy, but as a political scientist I think it’s a bad sign when political parties that condone violence against small-d democratic institutions are rewarded at the polls.

“Elections have consequences” is a common American political aphorism. In one way, the consequences of this election will be typical for the last generation or two of American politics. In another way, a party that I no longer recognize will internalize the lesson that it can say or do pretty much anything and not lose political power for long.