The Ideas Industry: How Pessimists, Partisans, and Plutocrats are Transforming the Marketplace of Ideas argued that three trends were transforming the public sphere: the erosion of trust in authority and expertise, the rise in political polarization, and the emergence of plutocrats with a vested interest in funding certain ideas. This led to a marketplace of ideas in which the barriers to entry were much lower but the barriers to exit were much higher. In short: it has become easier to introduce new ideas into the public sphere, but bad ideas just don’t die.

One of the critiques I received for The Ideas Industry when it came out was that I offered an analysis of the shifts in the marketplace of ideas without offering much in the way of solutions. It was a fair critique! The three trends I stressed were pretty systemic in nature, encompassing societal trends that went way beyond the marketplace of ideas. Asking an intellectual to solve those problems is akin to… well, asking Q to offer a practical solution to anything in Star Trek: The Next Generation:

If I had a hope, it was that the first two trends would reverse themselves in response to a crisis or shock that would remind citizens about the value-added that experts and technocrats could provide — much as what happened in response to similar conditions at the end of the 19th century.

In retrospect, this was foolish. It took a long time and a lot of shocks for conditions to change back then. Similarly, the United States has suffered through a series of shocks over the past seven years: Trump’s erratic presidency, the COVID-19 pandemic, the George Floyd protests, January 6th, the inflation surge, myriad signs of accelerating climate change, the war in Ukraine, and the war in Gaza. That is a lot of shocks. Unfortunately, they appear to have, for the moment, accelerated the trends I identified in The Ideas Industry.

Trust in institutions? It’s not great, Bob! Last summer Gallup’s Lydia Saad reported that the situation is pretty bad:

Most of the institutions rated this year are within three points of their all-time-low confidence score, including four that are at or tied with their record low. These are the police, public schools, large technology companies and big business.

Only four institutions have a confidence score significantly above their historical low: the military, small business, organized labor and banks. However, the lows for these institutions were recorded more than a decade ago, while the recent trend for each has been downward.

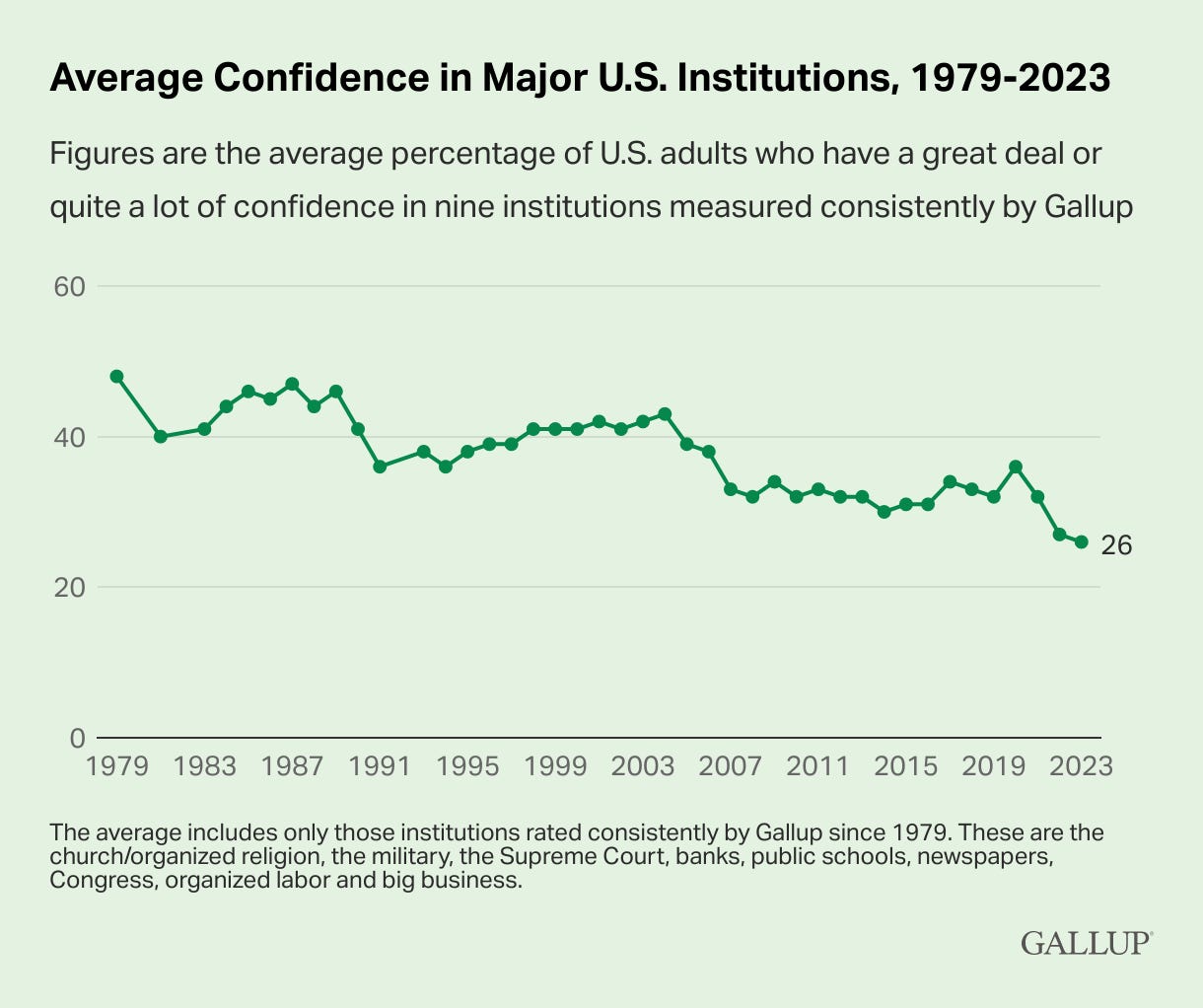

The historically depressed nature of today’s ratings is evident in the average confidence scores of nine institutions that Gallup has routinely tracked since 1979. That average fell to a new low of 26% this year. While down just one point from 2022, it is 10 points lower than in 2020.

Confidence has generally trended downward since registering 48% in 1979 and holding near 45% in the 1980s. It averaged closer to 40% in the 1990s and early 2000s before dropping to the low 30% range in the 2010s. Last year was the first time it fell below 30%.

Yeah, this chart is not encouraging:

Political polarization is also wreaking havoc on the ability of different components of the ideas industry to function. A decade ago, a majority of Americans from across the political spectrum believed that universities had a positive effect on the country. That was then. Five years ago the pronounced partisan split on university education was noticeable, with Pew showing 67% of Democrats believing universities had a positive effect but 59% of Republicans believing their effect was negative. By January 2024 Pew’s numbers had widened even further, with 74% of Democrats believing universities had a positive effect but 67% of Republicans believing their effect was negative. To be sure, the ivory tower is not a completely innocent bystander in this shift in public attitudes — but neither is it completely responsible either.

If you want another recent example, consider how Republicans reacted to Trump’s irresponsible NATO statements over the weekend — by rationalizing it away. According to the New York Times’ Maggie Haberman and Jonathan Swan:

After Donald J. Trump suggested he had threatened to encourage Russia to attack “delinquent” NATO allies, the response among many Republican officials has struck three themes — expressions of support, gaze aversion or even cheerful indifference.

Republican Party elites have become so practiced at deflecting even Mr. Trump’s most outrageous statements that they quickly batted this one away. Mr. Trump, the party’s likely presidential nominee, had claimed at a Saturday rally in South Carolina that he once threatened a NATO government to meet its financial commitments — or else he would encourage Russia to “do whatever the hell they want” to that country.

In a phone interview on Sunday, Senator Lindsey Graham of South Carolina seemed surprised to even be asked about Mr. Trump’s remark….

NATO countries’ spending on their own defense grew during the Trump administration, but it has expanded by an even larger amount during the Biden administration, after Russia invaded Ukraine.

It is the rise of the wannabe intellectual plutocrat that has been particularly bizarre in recent months, however. While sometimes these multi-millionaires are flogging ideas to advance their material self-interest, there are other drivers as well.

Perhaps no better person embodies this vainglorious trend than activist investor/wannabe intellectual Bill Ackman.1 There have already been multiple bursts of Ackman analysis in recent months. However, in a long New York cover story, Reeves Wiedeman profiled Ackman and revealed just what happens when a really rich dude believes he is also a really deep thinker.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Drezner’s World to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.