It Is a Bipolar World Whether Folks Like It or Not

The convenient fiction of multipolarity

Last week I participated in a Fletcher School panel about the expansion of BRICS. Rebecca Barrie of Tufts Daily wrote it up. It would be safe to say that the primary disagreement I had with my esteemed colleagues was whether the growth of BRICS represented a global shift towards multipolarity or not. As Barrie writes, my colleagues, “believe the BRICS expansion as an important step towards creating a multipolar world order, one where the West — and the U.S. specifically — isn’t the sole, dominating force on the global political stage.”

It would be safe to say that I disagreed: “What the members of the BRICS have in common is the desire for a more multipolar world. We live in a bipolar world. We have the United States on one hand and we have China on the other.” I’m hardly alone in making this assessment. For example, last month Jo Inge Bekkevold argued in Foreign Policy that, “Today, there are only two countries with the economic size, military might, and global leverage to constitute a pole: the United States and China. Other great powers are nowhere in sight, and they won’t be anytime soon.”

I bring this up because I see that Emma Ashford, a Foreign Policy columnist and a senior fellow with the Reimagining U.S. Grand Strategy program at the Stimson Center, is saying something different. Her latest column is a distillation of her recent Stimson Center paper with Evan Cooper. In both, she argues that the world is no longer unipolar and is not bipolar but rather multipolar.

Looking at a variety of data sources — which capture not just China’s growth, but also the major economic gains made by middle powers in recent years — the authors conclude that the emerging distribution of power is best described as a system of “unbalanced multipolarity.” Power is increasingly diffusing away from the superpowers toward a variety of capable, dynamic middle powers that will help to shape the international environment in coming decades.

Ashford correctly notes that this is an important debate to have. If the Biden administration acts like it’s in a bipolar world when in point of fact it’s a multipolar one, there’s a risk of making strategic choices — relying too heavily on allies that are not really allies, for example — that could backfire.

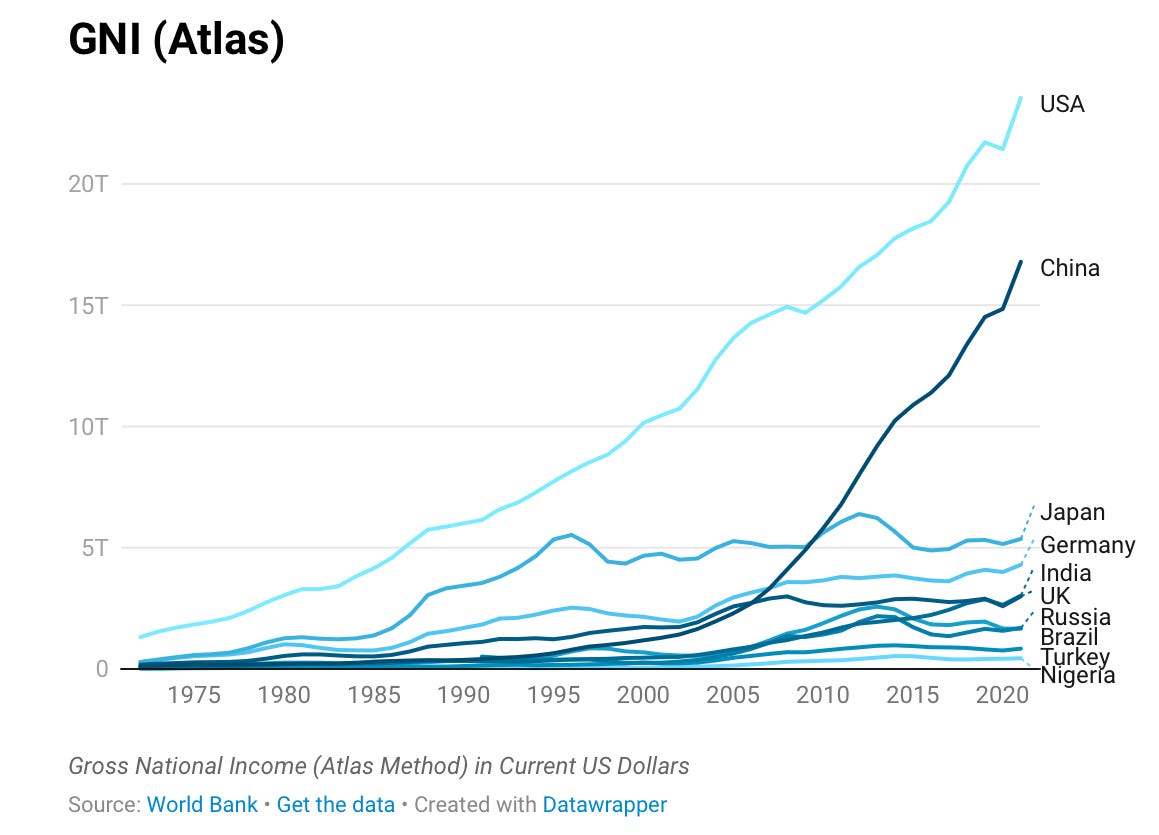

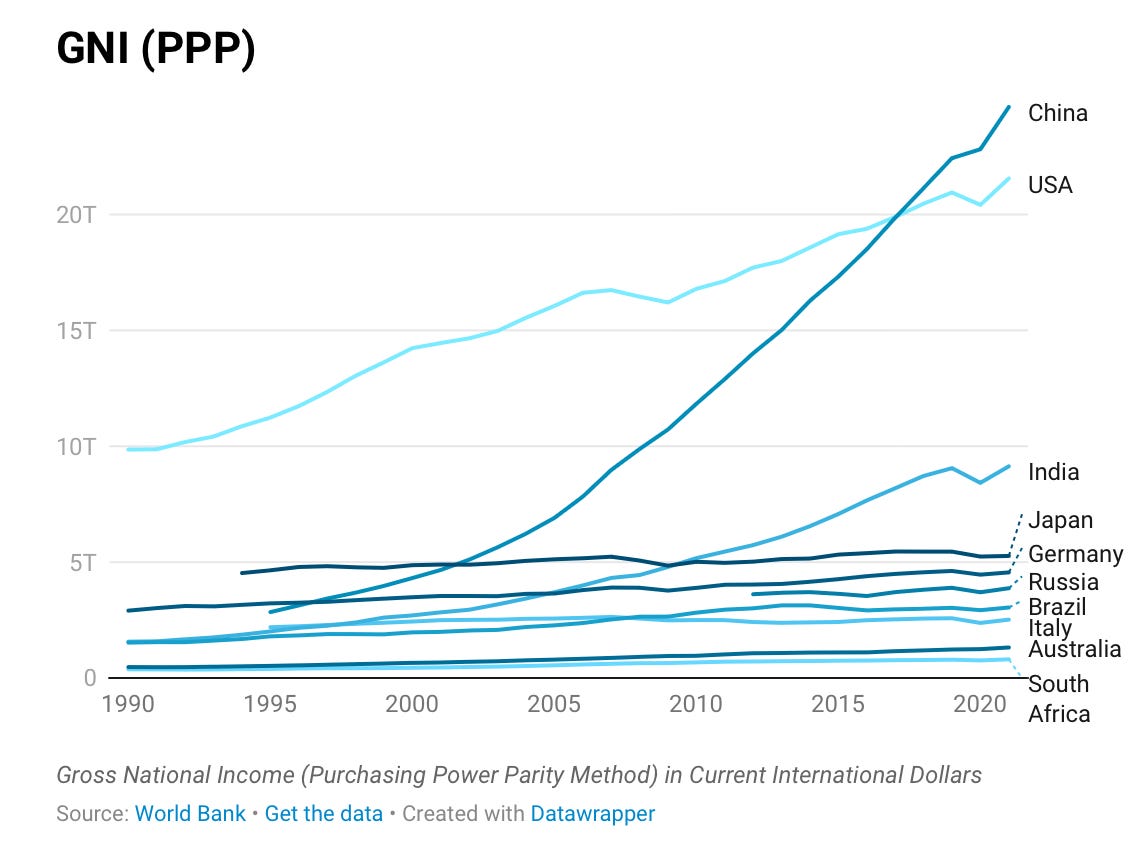

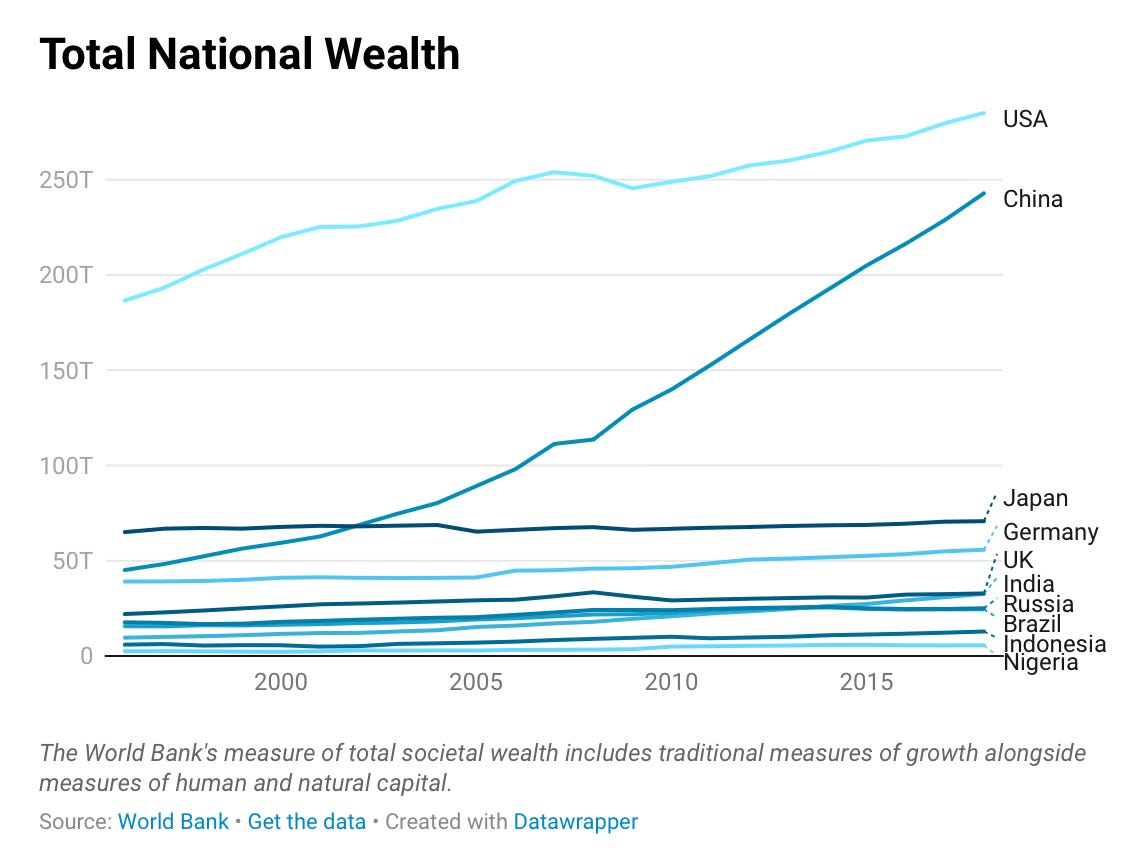

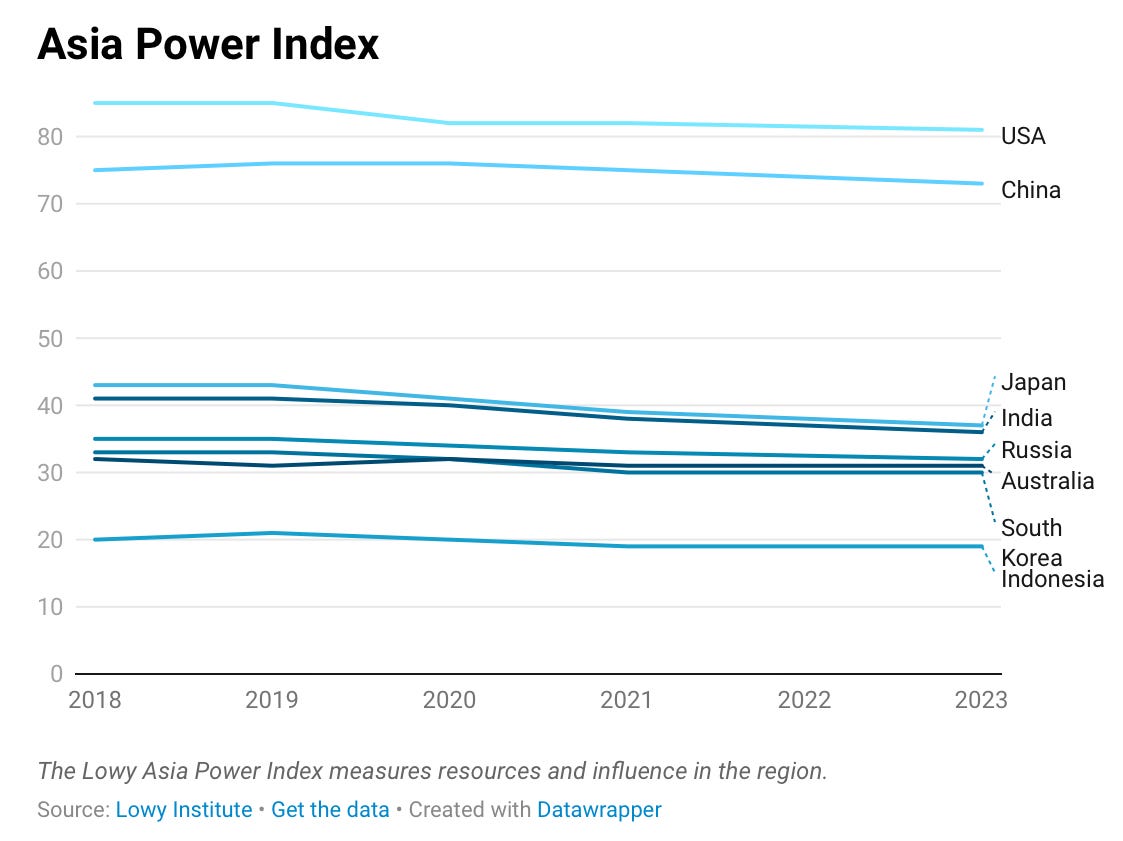

So how persuasive is Ashford’s argument? I think the meat of Ashford and Cooper’s paper is in their data section. They present multiple charts showing the history of the the distribution of power, with each chart relying on different metrics. They use seven different measures: GDP per capita, gross national income using market exchange rates, gross national income using purchasing power parity, GDP x GDP per capita (a metric used by my Tufts colleague Michael Beckley), CINC (a composite measure of national capabilities), total national wealth, and the Lowy Institute’s Asia Power Index.

Ashford and Cooper’s conclusions after looking at those charts is pretty simple:

These metrics suggest global power is diffusing not only to China, but also to other states….. As Mark Leonard describes it, “Beijing and Washington do not enjoy the same global dominance that the Soviet Union and the United States did after 1945. In 1950, the United States and its major allies (NATO countries, Australia, and Japan) and the communist world (the Soviet Union, China, and the Eastern bloc) together accounted for 88 percent of global GDP. But today, these groups of countries combined account for only 57 percent of global GDP. Whereas nonaligned countries' defense expenditures were negligible as late as the 1960s (about one percent of the global total), they are now at 15 percent and growing fast.”

This data thus suggests we are entering a period of unbalanced multipolarity, an international environment in which two major powers (the United States and China) are pre-eminent, but other second-rank powers (i.e., Japan, the United Kingdom, Germany, India, Turkey, or France) are also important players.

To put it gently, this is not what I see when I look at the data collected by Ashford and Cooper. Of the seven metrics, one — GDP per capita — suggests a multipolar world. One — Beckley’s metric — suggests a very unipolar world. One — the CINC measure — suggests China is considerably more powerful than everyone else, including the United States. The problem with the CINC measure is that it also has China eclipsing U.S. power in 1990, a claim that is so prima facie absurd that scholarship has been published on how utterly absurd it is.

Let’s dismiss those three measures as outliers. What’s left? Four metrics: gross national income using market exchange rates, gross national income using purchasing power parity, total national wealth, and the Lowy Institute’s Asia Power Index. Here are those charts — and you’ll never believe what they show:

Yeah, I’m not seeing much multipolarity in these charts. I see the United States and China standing head and shoulders above the other candidate great powers. Furthermore, I do not see those other states collectively gaining much relative ground compared to the United States or China.1

In their introduction, Ashford and Cooper note, “the statements of leaders around the world, U.S. partners and adversaries alike… openly argue that the world is entering a multipolar era.” They then quote India’s Narendra Modi, France’s Emmanuel Macron, Brazil’s Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, and Russia’s Vladimir Putin arguing that it’s a multipolar world. The thing is, however, that it is in the interest of all these national leaders to argue that it’s a multipolar world right now because a multipolar world makes these countries seem more powerful and influential than they actually are.

This buttresses a point I made at our BRICS panel: the idea of multipolarity is a very convenient fiction for all the BRICS members. It flatters the non-China members in granting them great power status, while allowing China to keep a lower profile and not shoulder more responsibility than it wants.

If Ashford or Cooper have stronger evidence I’ll be happy to see it — this really is an important empirical question. But looking at the data they provide, it does not look like a multipolar world. It looks like a bipolar distribution of power, which China and the United States as the poles. Other analysts and leaders might claim that it’s a multipolar world, but I don’t think the data is on their side.

One could argue that India might be a partial exception. in the GNI by PPP chart.

Yep. When I think of multi polar world China and the US come to mind but then....the mind goes blank. If any other nation is big enough to be called a 'pole' than being a pole doesn't really count for much and it's plain silly to think of them in the same league of 'the big two'.

Does it have to be one or the other? If the US' landscape analysis says "still bipolar if you have to choose, but middle powers increasingly not ignorable," does that set the stage for strategic intent differently than merely saying "bipolar"?

Also, I don't know what's in Asia Power Index but the other stuff is almost exclusively economic. Do other factors matter, e.g., "number of countries with nuclear weapons"?