Welcome to December 31, 2024, the last day of the year! That means it is time for Drezner’s World to award its annual Albies for the most important work on the global political economy published in all of 2024. This is the 16th year of the Albies, which means I have been doing them for a while and no one has sued me. I originally had the idea for the Albies in my first year of blogging for Foreign Policy. They migrated with me to Spoiler Alerts at the Washington Post and now reside here at Drezner’s World.

The constant about the Albies — and I cannot stress this enough — is that they represent my own idiosyncratic opinions. There is no committee of jurors or army of minions or gaggle of referees or conclave of Reviewer Twos assisting in these choices. Blame me for all the biases I bring to the table if I missed something important. The rest of the hard-working, super-fictional staff here at Drezner’s World are innocents.

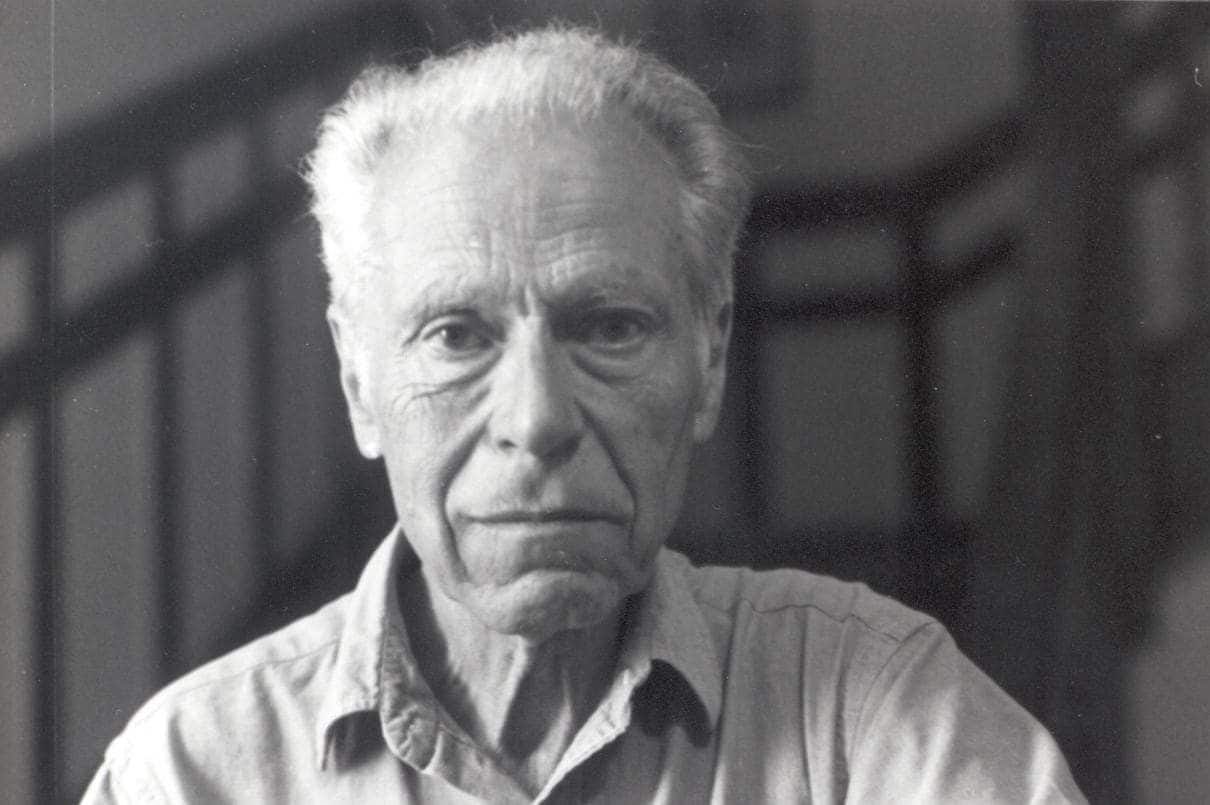

The Albies are named in honor of the late, great political economist Albert O. Hirschman. The important thing about an Albie-winning piece of work is that it forces the reader to think about the past, present or future of the global political economy in a way that can’t entirely be unthought.

In rough chronological order, here are the 10 Albie winners for 2024:

Richard Baldwin, “China is the world’s sole manufacturing superpower: A line sketch of the rise,” VoxEU, January 17, 2024. After looking at the OECD’s Trade in Value Added (TIVA) database early in the year, Baldwin concluded, “China is the now world’s sole manufacturing superpower.” In eight charts, he demonstrates the degree to which the rest of the world increasingly depends on Chinese manufactured components and goods — and the degree to which China’s dependency on the rest of the world has declined. As Baldwin concludes, “Politicians who indulge in loose talk about decoupling from China need a clear-eyed look at the facts…. Decoupling would be difficult, to say the least.”

David Autor, Anne Beck, David Dorn and Gordon H. Hanson, “Help for the Heartland? The Employment and Electoral Effects of the Trump Tariffs in the United States,” NBER Working Paper 32802, January. This is one of those papers that highlight the increasing cognitive dissonance between actual economic outcomes and political perceptions of those outcomes — a running theme of this year’s Albies.1 Autor et al demonstrate that the Trump’s administration’s 2018-19 trade war did not help import-competing sectors in the U.S. economy. Furthermore, retaliatory tariffs by other countries had deleterious effects on the U.S. agricultural sector. Nonetheless, Autor and his co-authors also find that “consistent with expressive views of politics, the tariff war appears nevertheless to have been a political success for the governing Republican party. Residents of regions more exposed to import tariffs became less likely to identify as Democrats, more likely to vote to reelect Donald Trump in 2020, and more likely to elect Republicans to Congress.” In other words, voters rewarded Trump with launching a trade war even though he failed to win anything.

Wilfred Chow and Dov Levin, “The Diplomacy of Whataboutism and US Foreign Policy Attitudes,” International Organization 78 (Winter 2024): 103-133. As the authors observe, whataboutism is a rhetorical tactic as old as the New Testament. Some governments will defend their violations of international norms by engaging in similar tu quoque arguments, accusing the accusers of similar behavior in the past. Chow and Levin ran survey experiments and came to a pretty simple conclusion: whataboutism works, at least when it is used on Americans. As a rhetorical response, whataboutism weakened U.S. public support for criticizing or commenting on the behavior of others. Furthermore — and to the authors’ surprise — “the efficacy of whataboutism is unaffected by the identity of its purveyor or its favorability in the eyes of the target public.” In other words, it doesn’t matter whether it is Russia or Canada employing whataboutism, it works regardless. This result is robust to proposed counter-messages by U.S. officials. This result might be the most 2024 finding among these Albies.

Gregory Brew, “Red Sea Shocks and the New More Stable Normal,” War on the Rocks, February 23, 2024. Richard Baldwin might be correct that decoupling from global manufacturing is difficult. The Houthi attacks on Red Sea shipping, however, highlight a contrary trend. As Brew writes, “The geopolitics of energy have undergone a transformation, call it ‘the great de-risking,’ brought on by progressive geopolitical shocks and shifts in the sources of supply over the last decade.” In essence, the Red Sea is no longer the critical waterway for oil, because geopolitics has created two different, more regionalized energy routes, and neither of them need the Red Sea much. This helps to explain how gas prices in the United States could steadily decline for most of this year.

Era Dabla-Norris, Daniel Garcia-Macia, Vitor Gaspar, and Li Liu, “Expanding Frontiers: Fiscal Policies for Innovation and Technology Diffusion,” IMF Fiscal Monitor, April. Industrial policy — so hot right now. Also so inefficient and ineffective. The authors of this chapter are not hostile to all forms of industrial policy: spending on sectors that generate strong knowledge spillovers to the wider economy, for example, are a net positive. Still, they point out that more directed government spending on specific sectors carries two significant opportunity costs. First, more targeted industrial policy usually means less spending on more fundamental basic research, which has the greatest spillovers. Second, political capture will tend to warp the welfare effects of any industrial policy; the greater the capture, the more likely such policies will lead to net losses even in a large market economy.

Marion Fourcade and Kieran Healy, The Ordinal Society, Harvard University Press. “We live in an ordinal society, a society organized toward, justified by, and governed through measurement.” Fourcade and Healy serve up a scabrous history of information management’s role in political economy and how the initial utopian ideas of technoliberalism curdled into firms exploiting their infrastructure monopolies to maximize data harvesting. Part of the reason this book works is that Fourcade and Healy acknowledge the positive utility that some of these arrangements generate, a “remarkably convenient, often delightful, and at times frightening” information order.

Soyoung Lee, “Resources and Territorial Claims: Domestic Opposition to Resource-Rich Territory,” International Organization 78 (Summer 2024): 361–96. The Trump administration is suddenly super-keen about imperial expansion, suggesting a return to 19th-century thinking about international relations, when territorial conquest and imperial extraction were perceived to be a means to promote the general welfare. Lee’s paper, however, suggests some counterintuitive limits to that impulse: “certain economic resources—particularly those such as oil and minerals, which can be relatively easily captured by specific groups—create domestic complications that often make it less appealing for leaders to initiate and sustain claims over the territory…. by making salient some domestic groups who may especially gain, resources can invoke suspicion among the general public about the true nature of the territorial conflict.” Lee’s paper does argue that more “barren” land are less likely to trigger this perception problem. It will be interesting to see how Lee’s argument plays out in 2025 — particularly for Trump, who has always stressed the economic benefits of any land grab.

The Washington Post’s 2024 series on The Money War. Back in late July the hard-working staff here at Drezner’s World wrote about Jeff Stein and Federica Cocco’s July 25th longform article, “How four U.S. presidents unleashed economic warfare across the globe.” This was the first in a series of longform pieces on economic sanctions and their effects, anchored by WaPo economics correspondent Stein. The same day Joby Warrick and Souad Mekhennet wrote, “Sanctions crushed Syria’s elite. So they built a zombie economy fueled by drugs.” This was followed by: Stein, Ellen Nakashima, and Samantha Schmidt, “Trump White House was warned sanctions on Venezuela could fuel migration,” July 26th; Stein and Claudia Méndez Arriaza, “Washington targeted ‘corrupt’ mines. Workers paid the greatest price,” September 27th; Stein and Stephanie Hays, “How a Russian oligarch’s $90 million megayacht landed in U.S. Custody,” October 23rd; Stein and Stephanie Hays, “Stein, Coco, and Peter Whoriskey, “A new Washington influence industry is making millions from sanctions,” October 24th; Warrick and Serhiy Morgunov, “Far from the front lines, a spy war rages over Russian weapons,” December 5th; and Stein, Hays, Cocco, and Nate Jones, “The U.S. seized a Russian yacht. Now you’re paying for it,” December 19th. In totality, this is some of the best journalism on economic statecraft that I have ever read. The Post deserves credit for devoting so many resources to this topic. Which makes this next Albie all the more depressing…

Jeff Bezos, “The hard truth: Americans don’t trust the news media,” Washington Post, October 28, 2024. I wrote at length about the Washington Post’s decision not to endorse a candidate back in October. In response to the fury that decision created among some WaPo subscribers, Bezos penned an op-ed explaining his decision. The op-ed is, to put it gently, a clusterfuck of contradictions. Bezos tried to frame it as a principled decision to correct the misplaced perception that the Post’s reporting is politically biased: “We must work harder to control what we can control to increase our credibility.” That could have been a valid point if Bezos had announced his decision at the start of 2024, or literally any other time except the general election season. Doing it when he did invited the perception that Bezos was knuckling under to Trump, a perception that he acknowledged later in the op-ed.2 Or, as he put it, “When it comes to the appearance of conflict, I am not an ideal owner of The Post.” In writing an op-ed justifying his decision to correct one perceived conflict of interest — and in the process fostering an even more pernicious perception of a conflict of interest — Bezos screwed the pooch. Someone, anyone in his retinue should have pointed out the logic pretzels contained in his craptacular argument. That no one did confirmed some fundamental truths of the ideas industry — in particular, that it is next to impossible to speak truth to money. Bezos’ volte-face is emblematic of the plutocratic response to Donald Trump’s return to power.

John Burn-Murdoch, “Democrats join 2024’s graveyard of incumbents,” Financial Times, November 7, 2024/Janah Ganesh, “Economics can’t explain all the anger of voters,” Financial Times, December 18, 2024. These last two columns capture perfectly the political schizophrenia of 2024, in that they both capture political truths that are somewhat difficult to reconcile. Burn-Murdoch’s column demonstrated pretty clearly how this was a year in which almost every incumbent party got shellacked at the ballot box — in fact, the Democrats did well compared to most other incumbents. Burn-Murdoch attributed “the current global anti-incumbent wave” to a combination of inflation and immigration. Ganesh’s column, however, offers something of a rejoinder, noting that populist parties have done well regardless of variations in individual country performance. Ganesh warns that, “the causal link between economic performance and political outcomes has broken down in both directions. Not only can a nation have a thriving economy to no obvious benefit to its politics, it can sustain awful politics without incurring economic damage.” In other words, as 2024 comes to a close, nobody knows anything and everybody thinks they know everything.

Is there a theme in this year’s Albies? I suppose it is the way that political perceptions increasingly guide actors to make decisions regardless of whether those perceptions are accurate or not — and that the perceptual gap can persist for a loooooong time. Yes, that is the perfect theme for 2024.

Congratulations to all the winners!

Also a running theme of Semafor’s collection of what media folks believed they got wrong, some of which are real lulus and some of which seem like the media learning exactly the wrong lessons from 2024.

Bezos’ explanation also exposed all the lies contained in publisher Will Lewis’ initial explanation for the decision.

Thanks for some great suggestions!

Thank you for keeping me sane in 2024. Best wishes to you and yours for 2025. I look forward to more sanity.