One of my favorite Spoiler Alerts columns was my 2016 advice for how to name a foreign policy doctrine. It included the suggestion, “Do you need a ‘neo’? Does the doctrine sound familiar? Can you affix “neo” to the adjective, like ‘neoliberal’ or ‘neo-Westphalian’? Then go for it!”

I bring this up because over the weekend David Leonhardt wrote a provocative news analysis with the headline, “A New Centrism Is Rising in Washington.” The subhed? “Call it neopopulism: a bipartisan attitude that mistrusts the free-market ethos instead of embracing it.” Ah, there’s the “neo”!

So Leonhardt has a name for his policy doctrine. Does he have anything more than that? Let’s take a look!

Strike one is that, as Leonhardt explained in his Monday newsletter, his editors asked him to, “make sense of this conundrum: A polarized country in which bipartisanship has somehow become normal…. I emerged from the project believing that the U.S. was indeed a polarized country in many ways — but less polarized than people sometimes think.”

Given the prominent and, um…. let’s say “contested” role of New York Times editors in The Discourse, this seems like a project designed to piss off everyone. But neither Leonhardt nor his editors are ginning something out of nothing. As Leonhardt observes, over the past five years or so, there has been some significant bipartisan legislation passed: “During the Covid pandemic, Democrats and Republicans in Congress came together to pass emergency responses. Under President Biden, bipartisan majorities have passed major laws on infrastructure and semiconductor chips, as well as laws on veterans’ health, gun violence, the Postal Service, the aviation system, same-sex marriage, anti-Asian hate crimes and the electoral process.” These are outcomes worth explaining.

Leonhardt’s explanation is “neopopulism.” From his longform Sunday read:

It has depended on the emergence of a new form of American centrism.

The very notion of centrism is anathema to many progressives and conservatives, conjuring a mushy moderation. But the new centrism is not always so moderate. Forcing the sale of a popular social app is not exactly timid, nor is confronting China and Russia. The bills to rebuild American infrastructure and strengthen the domestic semiconductor industry are ambitious economic policies….

The new centrism is a response to…. a recognition that neoliberalism failed to deliver. The notion that the old approach would bring prosperity, as Jake Sullivan, Biden’s national security adviser, has said, “was a promise made but not kept.” In its place has risen a new worldview. Call it neopopulism….

The forces that have created neopopulism are unlikely to disappear. They reflect enduring economic and international trends, as well as public opinion….

Trump’s heresy on trade and government intervention has made it easier for other Republicans to moderate their own positions. Daniel Schlozman, a political scientist at Johns Hopkins University, notes that Trump’s Republican Party demands loyalty on some topics, such as his false claims of election fraud. But the party is less homogenous on other issues than it used to be.

“That is the very weird paradox of this,” said Schlozman, co-author of “The Hollow Parties: The Many Pasts and Disordered Present of American Party Politics,” published this month. “There is more wiggle room to do ordinary policies like chips and infrastructure even as the party has moved right on the core democracy, will-we-count-the-votes-type questions.”

It is worth taking a beat here and pointing out something that should not have to be said, and yet here we are in 2024: if you are going to use a left-right spectrum on “will-we-count-the-votes-type questions,” that means you are saying Republicans have shifted towards an illiberal, undemocratic endpoint in which the only votes that should count are those that vote the right way. If the actual votes do not go your way, then you just lie about what happened.

If you care about, you know, democracy, this shift supersedes all other policy issues. It would be nice if Leonhardt had emphasized that point a bit more, but that was not his assignment.

So, what explains this neopopulism? Leonhardt serves up a political science-y, median-voter-theorem-style answer.

In part, this fusing of right and left is a sign that politicians are reacting rationally to voters’ views. Many political elites — including campaign donors, think-tank experts and national journalists — have long misread public opinion. The center of it does not revolve around the socially liberal, fiscally conservative views that many elites hold. It tends to be the opposite.

Americans lean left on economic policy. Polls show that they support restrictions on trade, higher taxes on the wealthy and a strong safety net. Most Americans are not socialists, but they do favor policies to hold down the cost of living and create good-paying jobs. These views help explain why ballot initiatives to raise the minimum wage and expand Medicaid have passed even in red states. They also explain why some parts of Biden’s agenda that Republicans uniformly opposed, such as a law reducing medical costs, are extremely popular. “This is where the center of gravity in the country is,” Steve Ricchetti, a top White House official, told me.

The story is different on social and cultural issues. Americans lean right on many of those issues, polls show (albeit not as far right as the Republican Party has moved on abortion).

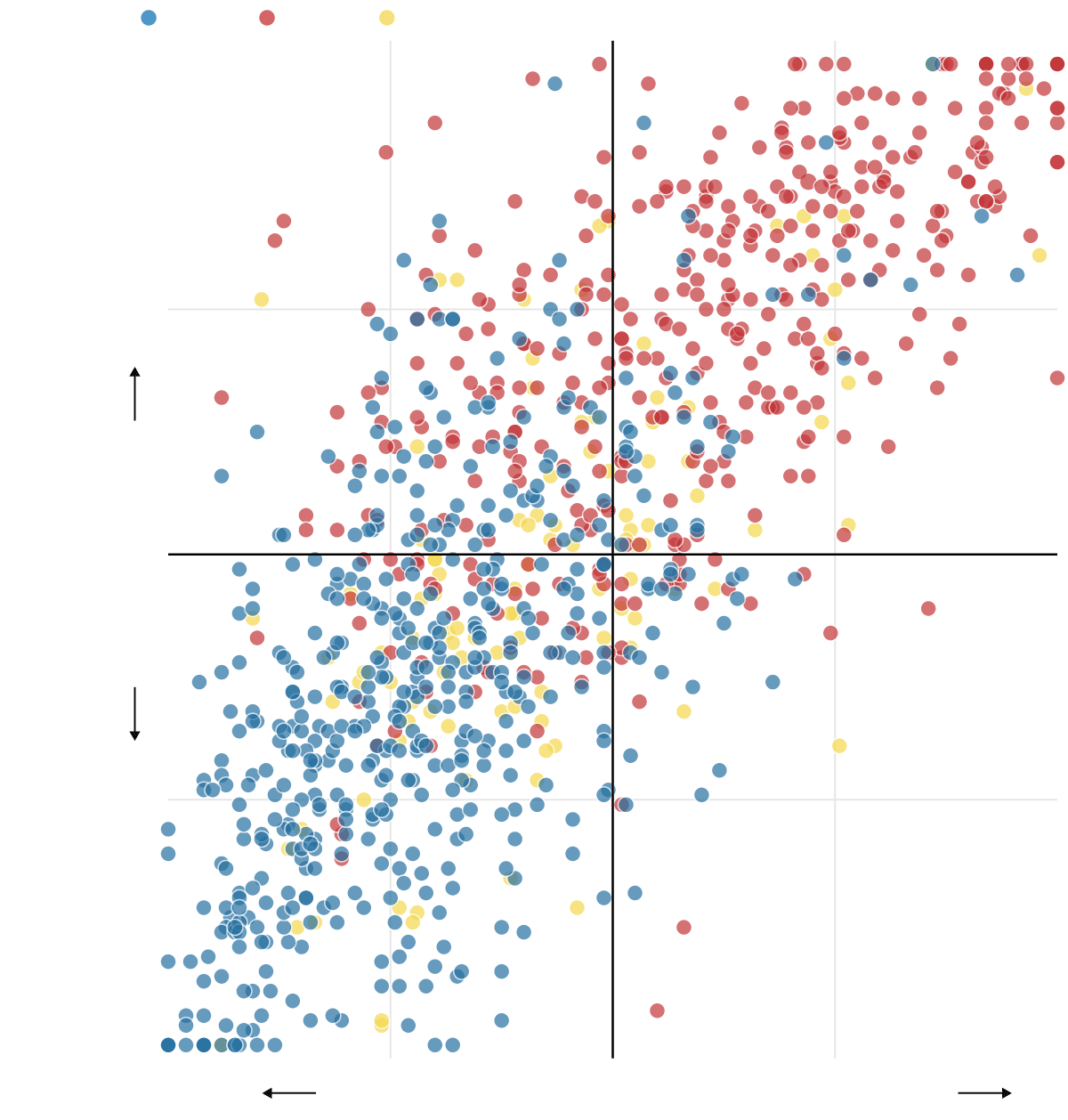

How compelling is Leonhardt’s theory? Well…. it’s not entirely wrong! When you poll American voters on whether they are fiscally conservative or liberal or socially conservative or liberal, you learn that there are a lot of Democrats (fiscally and socially liberal) and a lot of Republicans (fiscally and socially conservative). You can see that in the graph below (from the Times story, based on a 2023 Echelon Insight poll, but a result that reflects similar polling over the past decade or two), in which the bottom-left quadrant represents the Democratic quadrant and the upper-right represents the GOP quadrant:

Independent voters fall into either the neopopulist (fiscally liberal, socially conservative) in the upper left quadrant, or the neoliberals (fiscally conservative, socially liberal) in the lower right quadrant. Just a quick visual inspection of that graph shows there are more neopopulists than neoliberals, so it makes some sense to adopt positions closer to that median voter than the libertarian median voter as a means of winning a majority.1 And that shift is what has been happening for the past 15 years.

I have serious doubts, however, about two other elements of Leonhardt’s thesis. The first is his claim that the median voter has become more socially conservative over time. That is, how to put this, crazy talk. As Leonhardt acknowledges, every post-Dobbs referendum on abortion has signaled a more socially liberal preference. Look at the legalization of marijuana and the same trend emerges in which even red state voters are likely to favor it. Polling for diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) — shows far greater public support than the elite discourse usually posits. Indeed, the two concrete examples of bipartisan social legislation that Leonhardt cites in his story are gun safety and same-sex marriage — and both of those bills moved policy in a liberal direction.

The only area where voters shifted in a more conservative direction is on immigration. And that does lead to a central irony about neopopulism. Leonhardt writes that, “[neoliberalism] hasn’t worked out. In the U.S., incomes and wealth have grown slowly, except for the affluent, while life expectancy is lower today than in any other high-income country.” One can quibble with that assertion, but let’s just focus on the past few years for now. The U.S. economy has easily outperformed other high-income countries in terms of income and wealth. The key reason? All that darn immigration!

Leonhardt has captured a decided shift in American politics away from the neoliberal and towards something resembling economic populism. But I do not see any consensus shift towards more socially conservative views. The irony is that much of the economic growth folks want to ascribe to neopopulist policies is emanating from the vestiges of neoliberalism. And economists have serious doubts about the viability of economic populism as a generator of greater wealth and income.

Oh, and to repeat a theme: the GOP slide towards not caring about actual votes is more important than anything anyone writes about neopopulism.

It should be noted, however, that the neoliberal quadrant contains an awful lot of CEOs and plutocrats, a fact that forces them to make hard political choices.

The centrism essay is mostly speculative crap.

We’ve stopped noticing that the Republican Party is now fully oriented towards opposing democracy. The Republican Supreme Court is leading the way.